The court case file is not the only record that might shed light on a particular civil or criminal matter. Preserved by the Provincial Archives of Alberta and other archival institutions, records created by other people and organizations reveal their connections to or interests in the cases heard by Alberta’s courts and provide different perspectives. Some other records that you can explore include:

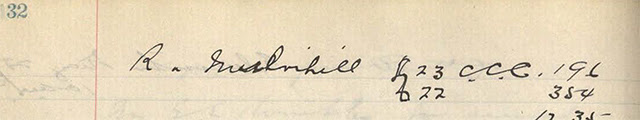

During the cases that they hear, judges often keep notebooks about the testimony and arguments. Some of these notebooks survive and are preserved both at the Provincial Archives and at other archival institutions.

Lawyers create their own files as they research and draft documents to be filed with the courts. Although rarely found in archives over concerns surrounding solicitor-client privilege, some lawyers’ case files have been preserved by archival institutions including the Provincial Archives of Alberta.

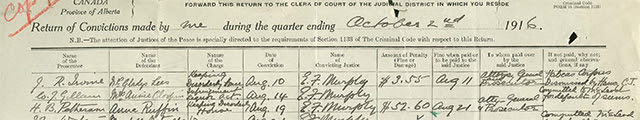

From the 1890s to the 1970s, the Government of Alberta required that magistrates and justices of the peace submit reports known as returns that outlined the cases that they heard and their judgments. Preserved by the Provincial Archives, the magistrate’s file may contain correspondence and other documents about cases that they heard.

Cases can be appealed from a lower level of court, such as a Magistrates’ Court or the Provincial Court of Alberta, all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. Each stage of the appeal contains information about the case. In some cases, you can work backwards from appeal files down to records from lower courts.

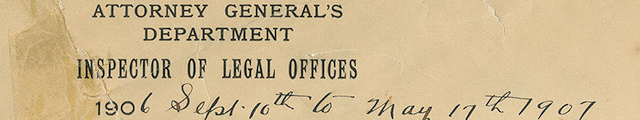

Alberta’s Department of Attorney General creates files pertaining to the administration of the court system and specific cases within it, whether it is a participant in the case or not. Although the earliest files are open for research without restriction, some materials are subject to Alberta’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

Alberta had its own police force from 1917 to 1932, and some departmental files and police notebooks have survived that might relate to court cases.

A person convicted of a crime might be sent to a provincial jail or prison, which then created records about its inmates. Although the earliest files are open for research without restriction, some materials are subject to Alberta’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

In cases where death did not occur by natural causes, the Office of the Medical Examiner will hold an inquest to determine the cause of death, which may lead to a criminal charge and a court case file. Although more recent records are maintained by the Office, the Provincial Archives preserves inquest and coroner files dating prior to 1925.

Much like modern media outlets, early Alberta newspapers avidly reported all activities occurring in the community, including the cases put forward for trial at the courts. Sensational murder trials, early divorces and appeals to higher courts outside Alberta usually received some press coverage.

Archivists and researchers occasionally have interviewed people with connections to important legal cases, such as judges or participants in the case, to provide another perspective about what happened. Although some oral histories have been digitized and even made available online, many others are only available by visiting archival institutions in person.

In addition to books about types of cases or notable cases, authors have written community histories, autobiographies, biographies of judges and lawyers, as well as academic theses that use, provide insight into, or analyze court records. Articles in academic and popular history magazines may also discuss court cases.